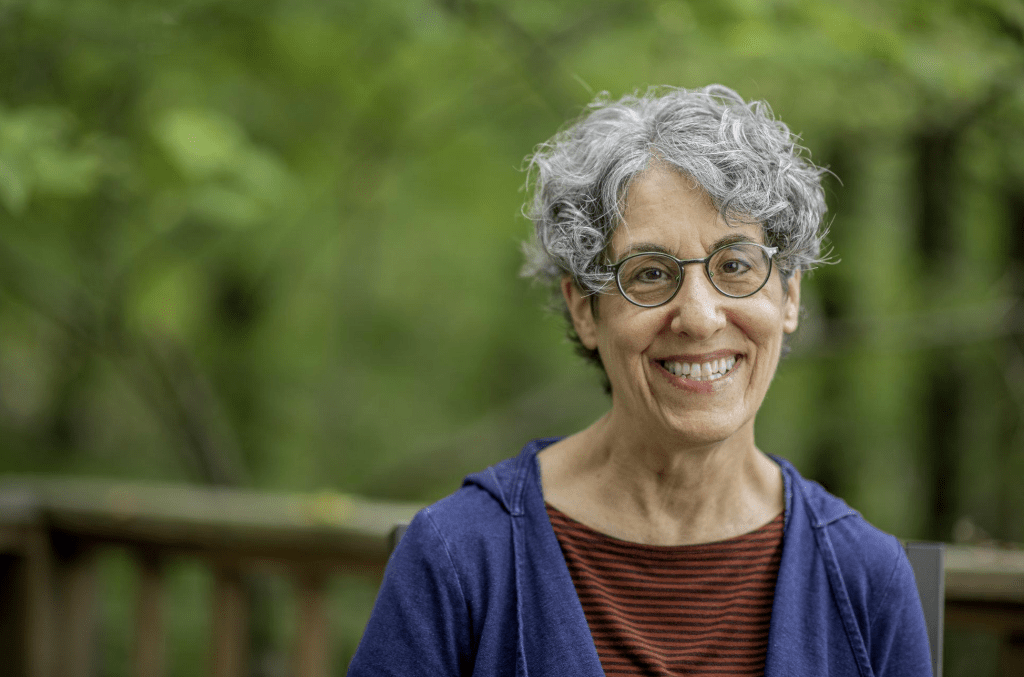

Researcher Explores End-of-Life Care Through Personal Lens

Jacqueline Wolf, Ph.D., chair of the social medicine department at the Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, co-authored a patient care case study article featured in the December issue of Millbank Quarterly. The article, co-authored with her brother Kevin Wolf, titled “The LakeWobegon Effect: Are All Cancer Patients above Average?” is a narrative analysis of their mother’s death from lung cancer in 2010.

The article is a first-hand account of the extensive medical care their mother Nancy Wolf received after being diagnosed with lung cancer, culminating in her death fifteen months later. Dr. Wolf and her brother wrote the article in alternating voices: the voice of the historian of medicine who also teaches ethics to medical students, and the voice of the actuary with expertise in healthcare costs and treatment efficiency.

Following their mother’s death in 2010, Kevin Wolf began researching more aggressively the treatment options suggested by oncologists during the fifteen months after Nancy received her diagnosis.

“Towards the end, I felt like the treatments were making less and less sense,” Kevin Wolf said. “After she died, I spent the next year researching every step of the process and the treatments that were offered to her, finding that they were, in many cases, inappropriate for someone in her condition.”

Kevin compiled his findings, sharing them with the family only. His only sister, Dr. Jacqueline Wolf, read the article and saw potential for an academic study. Working as a team, Kevin Wolf interpreted the statistical analysis, with Dr. Wolf leading the writing and theoretical analysis.

“It was very cathartic to let go of the personal side of the issue and see the situation as a medical professional,” Dr. Wolf said. “This article voices a global experience and poses some important questions, such as, when did society start to see heroic measures in end-of-life care as beneficial? In many cases— certainly in my mother’s case— it does more harm than good.”

The article moves chronologically from the diagnosis of Nancy’s stage IIB non-small cell lung cancer, step by step through each procedure and interaction with oncologists and other physicians, assessing communication behaviors and treatment options suggested to her at every appointment.

“My mother had no symptoms whatsoever from her disease until the three months before she died. During the twelve months previous, every symptom she had was from the medical care she was getting, and it was incredibly debilitating,” Dr. Wolf said. “If her cancer had been diagnosed when she became symptomatic, she would have died three months later— the exact time that she did. Catching it early did not extend her life at all, and she had a terrible and painful final year.”

The article assesses oncologists’ message framing when communicating bad news, finding that ambiguous and euphemistic terms are common. Many terminal patients leave their doctor’s office unaware of the reality of their diagnosis. Dr. and Kevin Wolf argue that the instinctive optimism conveyed to elderly, dying patients by cancer specialists prompts those patients to choose treatment that is ineffective and debilitating.

“Historically, the attitude about end-of-life care has changed dramatically over time,” Dr. Wolf said. “Where it used to be that good end-of-life care meant that you were made comfortable in your own home until your passing; now the attitude is that if we can extend life by two weeks with invasive treatments—no matter the physical and financial cost—we should do it.”

The article concludes by suggesting how oncologists can better help elderly patients who face a terminal illness to make medical decisions that are less damaging to them and less costly to the healthcare system. The researchers implore medical professionals and family members of failing elderly patients to communicate with ease and compassion, while still conveying a straightforward diagnosis.

In Nancy Wolf’s case, while her primary care doctor had done this, his decreased involvement in her care, coupled with other physicians overestimating her life expectancy and exaggerating treatment effectiveness, resulted in a delay in consideration of hospice care.

“Hospice is an incredibly compassionate way to take care of someone at the end of their life,” Dr. Wolf said. “Studies are showing now that hospice care actually extends life, in my opinion, more reliably than the invasive treatments. If you make a person comfortable in their own home, it is logical that it would extend life.”

The article also suggests the use of online educational tools and an ask-tell-ask method of relaying information to patients, which requires the patient to repeat the message as they perceive it, to ensure that the veracity of the diagnosis is being accurately communicated and understood.

Both Dr. Wolf and Kevin Wolf agreed that the brother-sister research team was unlikely to take on another research project together anytime soon, but were grateful for the experience to collaborate on an issue that was important to their family.

“We made the perfect team,” Dr. Wolf said of her collaboration with her younger brother. “I am a terrible mathematician and he is a terrible writer, and we both knew it. So we had a good understanding of the division of labor, and we complemented one another’s strengths and weaknesses.”

“Clearly it’s a personal article, but I think we were able to approach it pretty objectively,” Dr. Wolf said. “I want others to build upon the issues we have identified and bring about change, so that families don’t have to go through end-of-life care this way. This experience raises important questions, and I hope it will speak directly to, and impact, health policy.”

Leave a comment